Publication Date: 3 May 2018

The Blurb

Marinka wants to be an ordinary girl, with an ordinary life – a life that allows her to do what other living children do. Most of all, she wants to stay in one place and have friends. Real, living, human friends, not just her jackdaw and her special house.

Being the granddaughter of Baba Yaga, however, means that she must spend her days preparing for nights spent guiding the dead through the Gate, and moving from place to place whenever their house with chicken legs decides.

With her Baba and her house both set on her becoming the next Yaga, how can Marinka ever break free of her destiny and live the normal life she longs for beyond their fence of bones?

Cover illustration by Melissa Castrillon

The Review

A stunning reimagining of the Russian folk tale of Baba Yaga. Sophie has created a breathtaking adventure, that envelops the reader in a huge comforting hug. Marinka’s desire to have a life with the living, a life that goes against her destiny, is in turns courageous and selfish, yet utterly understandable – a wish that as the reader, I desperately hoped would come true for her.

But, it’s her love for, and determination to be reunited with her Baba that makes this such an enchanting and compelling read, which both breaks your heart and heals it. Courageous, hopeful and packed with love, The House With Chicken Legs shines like the stars on the blackest of nights.

The hauntingly beautifully internal illustrations by Elisa Paganelli add an extra layer of depth to this very special book that has it’s own place on the bookshelf in my heart.

Great for fans of:

- The Boy, The Bird And The Coffin Maker by Matilda Woods

- A Girl Called Owl by Amy Wilson

- The Girl Of Ink And Stars by Kiran Millwood Hargrave

Huge thanks to Fritha and Usbourne for sending me an early review copy and a stunning finished copy, and for inviting me to take part in The House With Chicken Legs Blog Tour.

Guest Post From Sophie Anderson

Vasilisa the Priest’s Daughter, on challenging stereotypes

‘In a certain land, in a certain kingdom…‘

In this Russian fairy tale, collected and published by Alexander Afanasyev in 1855, Vasily the Priest has a daughter named Vasilisa Vasilyevna.

Vasilisa wears men’s clothing, rides horseback, is a good shot with a rifle and does everything in a ‘quite unmaidenly way’ so that most people think she is a man and call her Vasily Vasilyevich (a male version of her name) …

‘… all the more so because Vasilisa Vasilyevna was very fond of vodka, and this, as is well known, in entirely unbecoming to a maiden.’

One day King Barkhat meets Vasilisa while out hunting, and thinks she is a young man. But one of his servants tells him Vasilisa is the priest’s daughter. The King does not know what to believe, so he invites Vasilisa/Vasily to dinner, then asks a ‘back-yard witch’ how he can find out the truth.

The witch tells the King to hang an embroidery frame on one side of the room, and a gun on the other, and that a girl would notice the frame first, and a boy the gun. But when Vasilisa comes to the palace, she only berates the King for having ‘womanish fiddle-faddle’ in his chambers.

So, the King asks the witch for another test, and invites Vasilisa/Vasily to dinner again. The witch tells the King to cook kasha (porridge) with pearls in and explains a girl would put the pearls in a pile, and a boy would drop them under the table. But when Vasilisa comes to the palace, she only berates the King for having ‘womanish fiddle-faddle’ in his food.

Once more, the King asks the witch’s advice, and invites Vasilisa/Vasily to another dinner. The witch tells the King to suggest a bath after dinner, as a boy would visit the bathhouse with the King, but a girl would refuse.

Vasilisa agrees to go for a bath, but is in and out before the King has changed, and returns home leaving only a note for the King:

“Ah, King Barkhat, raven that you are, you could not surprise the falcon in the garden! For I am not Vasily Vasilyevich, but Vasilisa Vasilyevna.”

‘And so King Barkhat got nothing for all his trouble; for Vasilisa Vasilyevna was a clever girl, and very pretty too!’

I find the narrator’s last comment about how pretty Vasilisa is entirely irrelevant; although when I’m in an optimistic mood I try to interpret that the narrator has recognised there are diverse types of beauty beyond stereotypical ones. That line aside, I love this tale!

Vasilisa the Priest’s Daughter was one of the first stories I heard that broke fairy tale stereotypes. Vasilisa was a young girl, but she was strong and independent; she was happy with who she was, and with being different from other ‘maidens’; she wasn’t in need of rescue, and when she met the King she didn’t swoon or fall into his arms or marry him – she resisted his attempts to define her and rode off into the sunset unchanged from who she was at the start of the story. Vasilisa was complete and content on her own. It was such a refreshing tale to hear.

Russian fairy tales, like many other groups of fairy tales, are rife with stereotypes; the ugly, evil, old woman; the handsome brave young hero; the beautiful princess, who is often no more than a prize for the young hero; and the abused peasant girl who may, if she is hardworking and resourceful, rise to the giddy heights of becoming the wife of a tsar.

Even as a young child, these stereotypes felt deeply wrong. I knew real life was different. Elderly ladies were not, in my experience, ugly or evil. Young boys were not always brave heroes with a desire to prove their strength in battle and marry princesses. And young girls were certainly more than prizes for boys; and aspired to much greater things than becoming solely the wives of royals.

Tales such as Vasilisa the Priest’s Daughter offered a tantalising glimpse of something different. They felt real and true, and I longed for more of them. Stories that broke stereotypes seemed to be few and far between, but in the rare and wonderful moments I heard them I knew they touched on an important truth: that stereotypes need to be challenged.

Thankfully, as I have grown older, I have discovered many more wonderful fairy tales from all over the world that break stereotypes.

I believe it is hugely important readers are given the opportunity to discover and share these tales, as they represent a far more accurate view of the world and give a much wider range of individuals an opportunity to see themselves in a story. And when we do come across stereotypes in stories, I think we all have a responsibility to discuss and challenge them.

Vasilisa the Priest’s Daughter can be found in one of my favourite adult fairy tale collections, alongside plenty of other tales that break stereotypes: Angela Carter’s Book of Fairy Tales, written by Angela Carter, published by Virago.

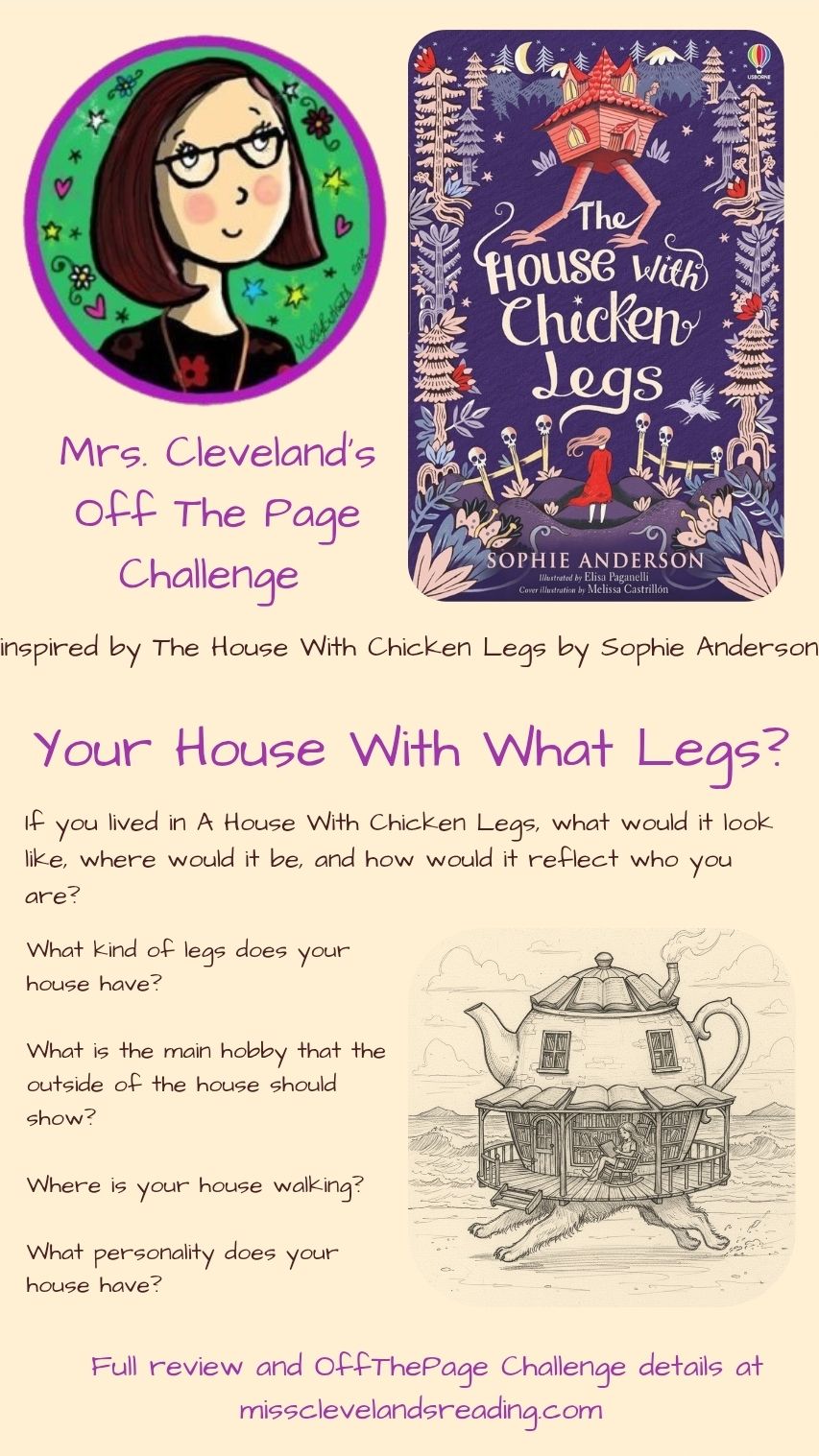

The Off The Page Challenge

Marinka’s house is a fully sentient character that adapts to and interacts with its residents. It got me thinking, if I lived in a house with chicken legs, what would it look like? How would it adapt to provide for, and protect me?

So, my challenge inspired by The House With Chicken Legs Runs Away is to draw your very own House.

- What kind of legs does your house have? Are they scaly dragon legs? Dainty flamingo legs? Powerful ostrich legs?

- What is one main hobby you love that should be visible from the outside? Are there two equally important that could be merged together?

- Where is your house walking right now? Through a city? Over the ocean? Through a forest of giant candy?

- What is your house’s personality? Is your house grumpy? Happy? Shy? Use the eyes (windows) and a mouth (door) to show its mood.

Don’t worry about the house being perfectly balanced. It’s magical, so it can be top-heavy or leaning if you want it to be.

Now, set your 10 minute timer and get creative!

3 thoughts on “The House With Chicken Legs by Sophie Anderson”